Where it's actually - short-term memory is 30 seconds to a minute. They sort of portray short-term memory as something from an hour ago or, like, that same day. That's sort of one of those mainstream ideas of how memory is structured and works, which is not quite correct - in that short-term memory - you see a lot of films and, like, TV shows. I mean, from how you describe it, it holds less than I even thought.īURNETT: Yeah. And short-term memory really doesn't hold very much. GROSS: In writing about memory, you write about the difference between short-term memory and long-term memory. Because our memory is the only record of it, that often goes unnoticed. And that seems to be happening constantly - that we think back on things and we sort of interpret them in different ways to make us feel better about ourselves - make us feel more accomplished, more involved, more capable and more important than we actually were. So the actual underlying memory is replaced by this updated version that you have created to convey something which makes you look better. But every time you do that, the memory itself - it's got a good chance of itself being edited. Or we'll make it a bit more impressive as a story. We'll embellish it slightly to make us look a bit better. But all of you will think that's just someone lying to try and look better.īut a lot of research suggests that we actually - whenever we remember something, we will tend to embellish if we're telling someone about it. And oh, the obvious joke is that they didn't really.

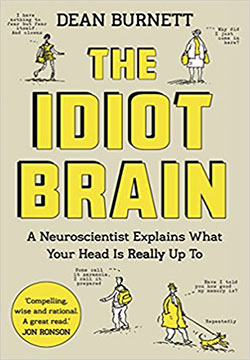

What's an example of what you mean there?īURNETT: Well, I think the classic example is like someone claiming they caught a fish this big, holding their arms out. And you say your memory is egotistical - that the brain tweaks and adjusts the information it stores to make you look better. So the computer altered it for you - to suit your purposes, to suit your preferences. GROSS: So in that analogy that you make between the brain and a computer, you say your brain would be like a computer that decided it didn't really like the information you'd stored. He writes the science blog "Brain Flapping" for the British newspaper The Guardian. He lives in Wales, where he's based at Cardiff University's Center for Medical Education and teaches in the psychiatry department. But according to my guest, neuroscientist Dean Burnett, that's only true if you imagine a computer that decided some information in its memory was more important than other information for reasons that were never made clear or a computer that filed information in a manner that didn't make any logical sense or a computer that kept opening your more personal and embarrassing files without being asked.īurnett is the author of the new book "Idiot Brain: What Your Head Is Really Up To." It focuses on some of the more illogical behaviors the brain produces.

People often think of the brain as being like a computer.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)